Shishkin as a painter (A. Savinov)

Russian landscape painting of the nineteenth century constitutes a significant chapter in the history of Russian culture. The landscapes created in the first half of the century by Alexei Venetsianov, Ivan Aivazovsky, Sylvester Shchedrin, and Alexander Ivanov are lyrical implementations of an optimistic, humanist perception of nature. The flowering of realist art in the second half of the nineteenth century served to deepen the content of landscape painting: the artists of the genre found new means of expression as they turned their efforts to creating a truly Russian image of nature. Alongside such masters as Alexei Savrasov, Fiodor Vasilyev, Arkhip Kuinji and, somewhat later, Isaac Levitan and Konstantin Korovin stands the name of Shishkin, whose creative career spanned almost the entire latter half of the nineteenth century. Shishkin's popul arity has withstood the test of many decades: he is to this day one of the most revered of Russian artists.

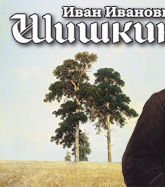

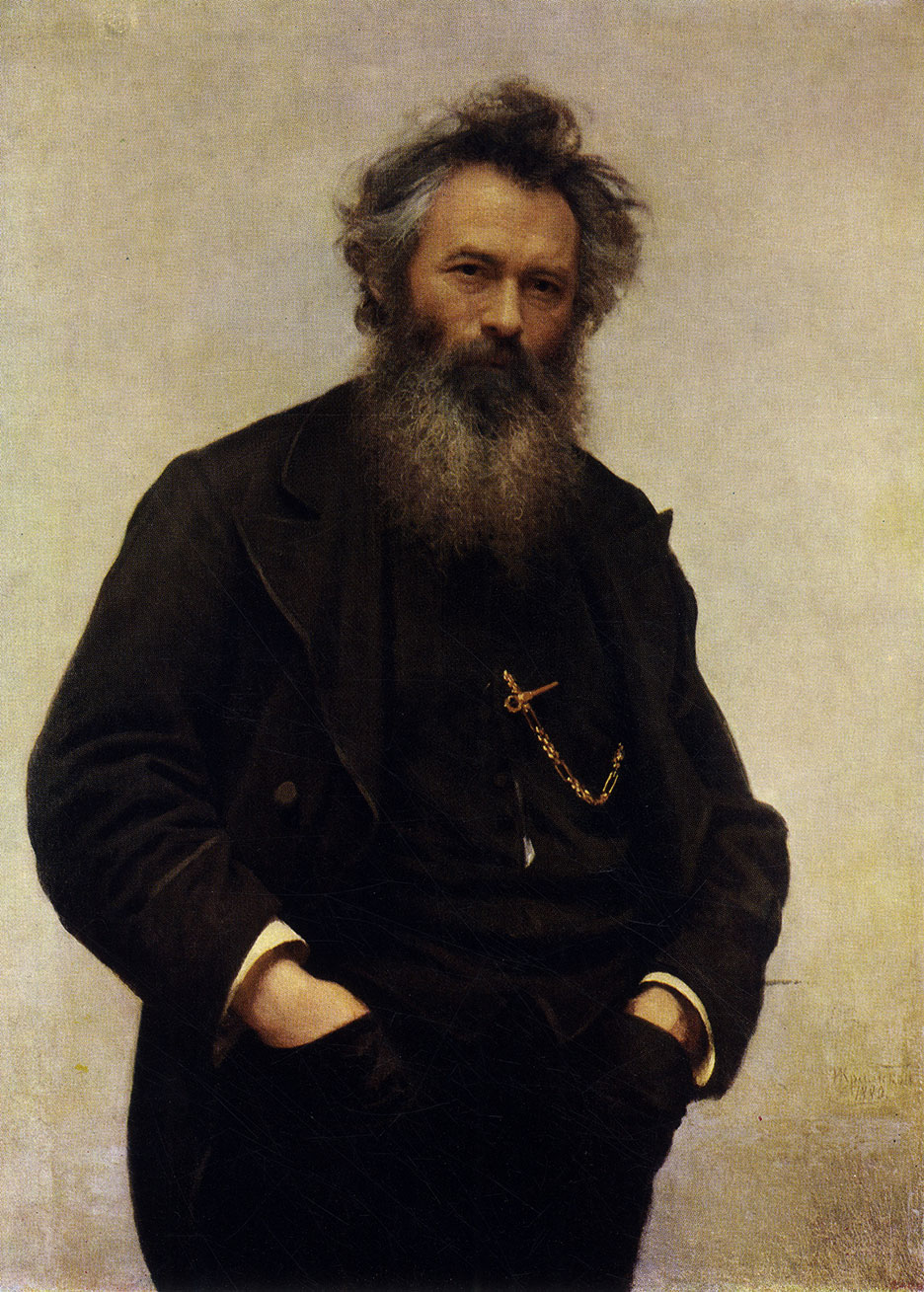

Portrait of Shishkin by Ivan Kramskoi. 1980. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin was born in the town of Yelabuga (near the Kama river, a tributary of the Volga) on January 13, 1832. Under the influence of his father, an amateur archaeologist and a connoisseur of local lore, the future artist learned to deeply appreciate the history and scenic beauty of his native land, and to love the picturesque banks of the Kama and the endless forests of the Viatka province. Shishkin's first serious encounter with art was at the Moscow School of Painting and Sculpture. One of his teachers there was Professor Apollon Mokritsky, formerly a pupil of Venetsianov, who did much to encourage and develop the young man's talents. Shishkin read widely during those years, reflected on the meaning of art and came to the conclusion that the artist is duty-bound to study nature and reproduce it faithfully in his works.

In 1856 Shishkin, by then an artist with established creative preferences, enrolled at the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts. The young artist was not much impressed by the Academy's contrived landscapes; he spent most of his time painting from nature in the vicinity of the capital or amid the austere beauty of Valaam, an island in the northern part of Lake Ladoga.

Woman with a knapsack on her back. 1852 - 55. Lead pencil and water-colours on paper. 22.8×19.7 cm. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

Graduating from the Academy with a gold medal, Shishkin was granted a scholarship that entitled him to take a trip abroad, and went to Europe. In Dusseldorf, then a major art centre, he became known for his ink drawings which caught the public eye by their exquisite craftsmanship. These somewhat arid, sharply delineated pieces share an affinity with the master's early paintings. The best of these drawings is View in the Vicinity of Düsseldorf (1865), for which the artist was awarded the title of Academician. Shishkin did not seek easy success; he was not attracted to the spectacular Swiss or Italian views that were then all the rage. Studying nature in depth had opened his eyes to the beauty of the flat northern landscape. However, the ability to paint nature well was not for Shishkin an end in itself: the goals he pursued in his artistic endeavour coincided with those aspired to by the progressive forces in Russian art.

Peasant and peddler. 1855 Water-colours on paper. 40.4×30 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

On returning home he was immediately accepted into the circle of young artists, the future Itinerants (Peredvizhniki), who had not long ago, in 1863, broken with the conservative Academy of Arts. He struck up a friendship, one which was to last many years, with Ivan Kramskoi, the ideological leader of Russian democratic art of that period. Shishkin well understood that the function of landscape painting is not only to convey nature in all its aspects, but to reflect the life of one's native country arid express the ideals of the time as well. The motherland is the prime theme of his canvas Midday in the Neighbourhood of Moscow painted in 1869. Depicted is a typically Russian landscape - endless fields under a high, pale sky, a road winding through the ripening grain, with peasants walking along it. By peopling the landscape with human figures the artist here transcends, as it were, the limits of the genre.

Under the influence of democratic artists Shishkin's works gradually grew richer in content and acquired specifically Russian features. At the same time, he resorted less and less to the highly detailed manner of his earlier pieces. The creative maturity achieved by Shishkin is especially evident in two pictures of 1872 - Pine Forest in Viatka Province and Backwoods. The first of these is a story of the Russian landscape, told in a truthful and leisurely fashion. In it, the artist incorporates images familiar to him since childhood: a mast-tree grove, a glade amidst the trees, a pine with a bee-house hanging from one of its branches, and two bears sitting near by. There is as yet no attempt here to blend the various elements of the landscape into a painterly whole. The other work, Backwoods, for which he was made professor, is more integrated. The dense forest with its stunted, moss-grown trees, the withered branches, rotten snags and pools of stagnant water are all an integral part of the same theme. There are no wide expanses in the picture, no highlighted compositional centre; the canvas does not aspire to decorativeness, and this is precisely why it was seen as a challenge to the "invented landscapes" (in the words of Kramskoi) of the academic school.

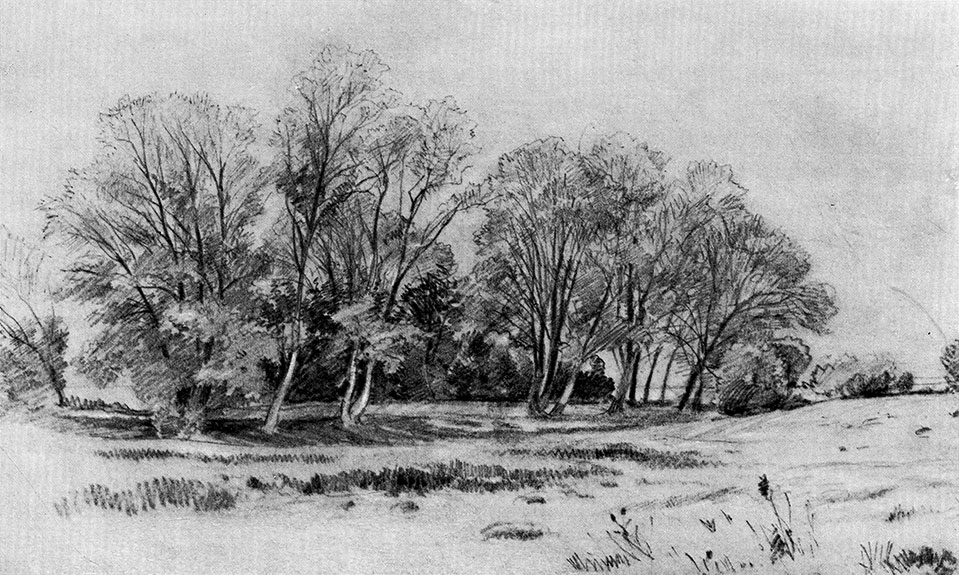

Trees in a field. Bratsevo. 1866 Black chalk on tinted paper. 26.5×42.8 cm. Museum of Russian Art, Kiev

Also new and unusual for the time is the painterly manner of the picture. The many shades of the prime colours, the complex colour gradations, and the variety of methods used to apply the paint all bear witness to the artist's painstaking efforts at achieving expressiveness in the depiction of nature.

Landscape with a herd. Sketch for the similarly entitled picture (1862) Lead pencil on paper. 23.3×36.5 cm. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

Shishkin was the first Russian landscapist in the second half of the nineteenth century to attach such tremendous significance to the plein-air study. To him, the study was at once a way of deepening his knowledge of nature, a useful exercise in improving his professional skill and a basis for the creation of finished landscape compositions. Kramskoi wrote in 1872: "Shishkin simply amazes us by his ability, doing two or three studies a day, and such complex ones too... Out there, face to face with nature, he is in his element, he is bold and clever and unhesitant: out there he knows everything... he is by himself a school..."

Shishkin's large and small-size studies sometimes contain a complete landscape motif, sometimes a mere detail, but whether the subject is a vast expanse of countryside or a goutwort-covered forest nook the artist always lends it an organized compositional arrangement. This is because he regarded the study not as a note for the memory but as a finished work of art.

His ceaseless plein-air sketching developed in Shishkin a talent for seeing deep into nature, differentiating between its various states, and viewing it from a new angle. By the 1870s, he was already producing works that depicted the transient states of nature, be it evening, twilight or sundown.

Throughout his creative life, Shishkin's cardinal theme was the beauty of his native land. This theme is cleverly and simply implemented in one of his classic works, Rye (1878). The vast golden fields and the solemn rhythm of the tall trees receding towards the horizon symbolize the essence of Russia and the artist's belief in her greatness.

The evolution of Russian painting in the 1870s laid the groundwork for its upsurge in the following decade. It was in the 1880s, notwithstanding the political reaction in the country, that Ilya Repin, Victor Vasnetsov, Vasily Vereshchagin, Vasily Polenov and other progressively-minded realist artists produced their ideologically incisive and artistically expressive canvases. This brilliant array of painters also includes the name of Shishkin, His finest works of the 1880s are a blend of epic majesty and truly heartfelt emotion, as, for example, Stream by a Forest Slope (1880) and especially Amidst the Spreading Vale (1883). Its title is the first line of a poem by Merzliakov, which became a folk song in the nineteenth century.

The mighty oak standing alone in a field is an image of manly and poignant beauty that leaves no viewer unimpressed. Shishkin lends this landscape a new compositional twist in that the viewer is not made to look at the scene from the outside but to become, as it were, a part of it, to stand on the threshold of the familiar world surrounding the artist. This kind of compositional arrangement which eliminates all distance between real and painterly space was used in the 1880s by Repin, Surikov and Serov.

The restraint of Shishkin's early works gave way to a heightened emotionality in his works of the mid-1880s. The landscape imagery of such pictures as The Forest in Spring, Woodland Vistas (both 1884) and Misty Morning (1885) evokes a deeply sentimental feeling in the viewer as he absorbs a vision of nature dear to his heart. Shishkin here displays exceptional craftsmanship in the way he combines different spatial perspectives and contrasts the solidity of objects in the foreground with the ephemeral aspect of far-away objects shrouded in mist.

A fallen oak on a rocky shore Lithograph.* 12.5×18 cm

* (All lithographs and etchings reproduced are from the Russian Museum, Leningrad. For etchings, only the size of the impression is given)

The evolution of Russian culture imposed new creative tasks on the country's artists. Shishkin's landscapes appeared at the time when Kramskoi called for a "lively, striking painting", when Repin had already created his Religious Procession in Kursk Province and Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan, and when Surikov was working on the canvas The Boyarina Morozova, a picture highly dramatic in its content and innovative in the way it is resolved.

Rye. Sketch for the similarly entitled picture (1878) Lead pencil on paper. 14.4×23.6 cm. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

In 1886 Shishkin produced two pictures, The Holy Spring Near Yelabuga and Oak Grove, in the style he had developed over the years. This style, in which the paint was applied in a thick layer, is distinguished by the precision of its colours and its meticulous characterization of the objective world. That same year, however, saw the completion of a third piece, Pine-trees Lit Up by the Sun. Never before had Shishkin produced a work so suffused with light, so translucent and pure in its colouring. A consummate sketch that is perceived as a finished picture, it is a lyrical and optimistic piece, with a profusion of golden, pale green, azure and velvety dark-green dabs of colour. Shishkin's work during the 1880s, drawings and paintings alike, is characterized by a specific method of portraying light which tends to emphasize the richness of the tones and to enliven the various colours with shades of differing density. His sunlight infiltrates the forest depths or appears in flashes amid the distant trees. Shishkin used light to lend emotional cohesiveness to intricate landscape compositions. This is vividly exemplified in the canvases Oak and Oak Grove (both 1887) where the trees, enveloped in light and air, are portrayed in a sculptural manner, and in several studies which bring out all the radiant beauty of nature's modest little nooks. Never once, however, does the artist indulge in the play of light at the expense of material detail: in addition to studying the effect of light on various objects he produced a succession of sketches in a continuing exploration of the forms and texture of trees, flowers and grass.

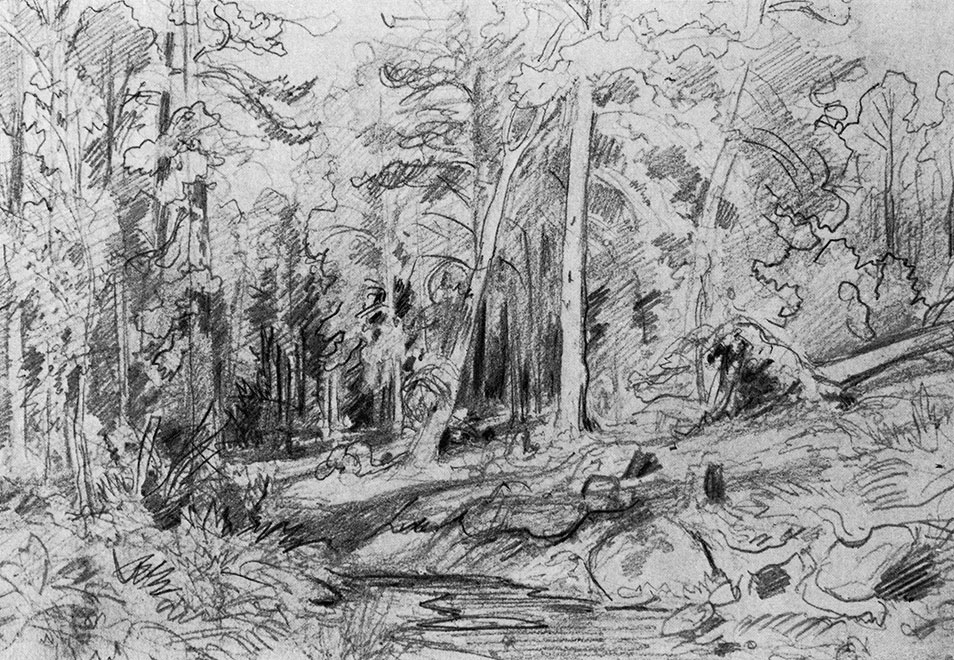

Pine forest. Sketch for the picture Pine Forest in Viatka Province (1872) Lead pencil on paper. 18.1×26.8 cm. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

These versatile activities had as their result the canvas Trees Felled by the Wind (Vologda Woods) (1888), a work which reflected different facets of the artist's talent. The firtrees have a majestic and solemn aspect as they recede into the sombre depths of the forest; in the foreground, lit up by the sun, are trees felled by a storm, their half-rotted trunks overgrown with moss. This sad scene of the doom which has befallen the woodland giants is enlivened by the presence of several young fir-trees. Endowed with a subtle feel for nature, Shishkin places the trees that have stood there for centuries side by side with clusters of mushrooms that have just emerged from the ground, and with quick flashes of light on the waters of the stream. The concept of the multifariousness of nature that strikes a responsive chord in man is here expressed much more sweepingly and evocatively than, for example, in Backwoods (1872).

Midday in the neighbourhood of Moscow. Bratsevo. 1866 Oil on canvas. 65×56 cm. Picture Gallery, Astrakhan

The triumph of life is also the subject of the well-known canvas Morning in a Pine Forest (1889). The theme was suggested to Shishkin by the Itinerant artist Konstantin Savits-ky, who painted the bears in the picture. The cubs are playing on the trunk of an old pine blown down by the wind. One of them, head inclined, seems to be listening to the sounds of the awakening forest; the tops of the trees are lit up by the first rays of the sun, the background is enshrouded in a blue morning mist beyond which teems a life we cannot see. Blended into one in this canvas is a story told in detail and a vague allusion to what exists beyond the reach of our vision.

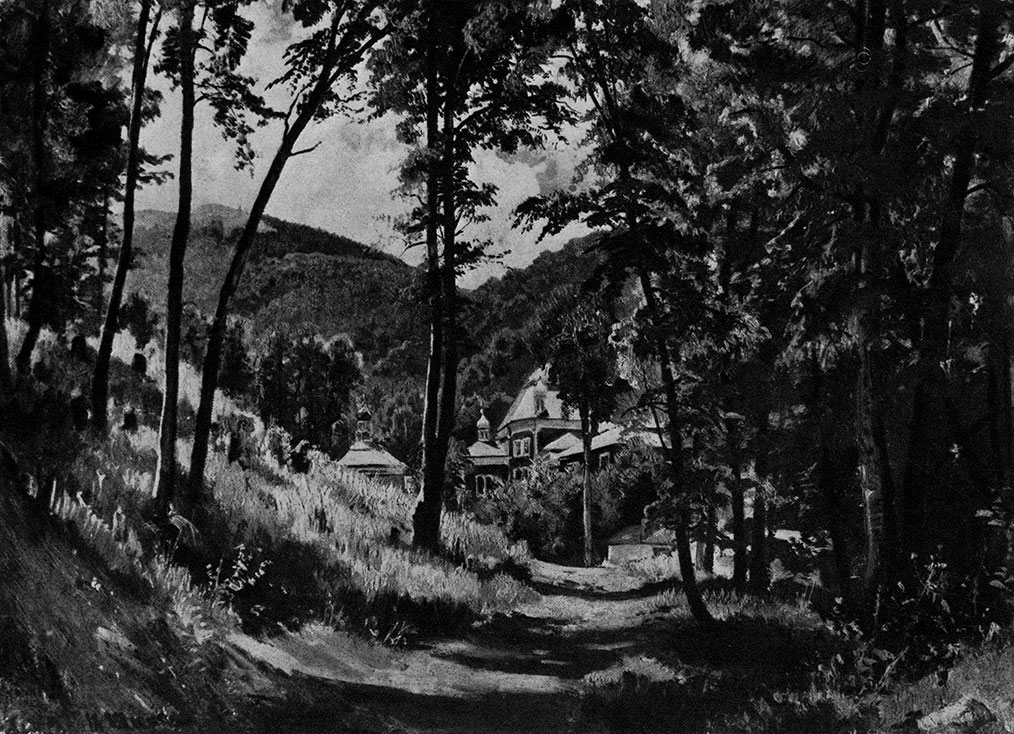

The crimea. The monastery of sts Cosmas and damian. Not earlier than 1879 Oil on cardboard. 37×52 cm. The Savitsky Picture Gallery, Penza

The advent of the 1890s saw Shishkin at the peak of his powers: every Itinerant exhibition was bound to have several of the master's canvases on display. It looked as if there was no complex painterly problem the artist could not solve. In a short period of time he produced several dissimilar works: Countess Mordvinova's Forest. Peterhof, Rain in an Oak Forest and In the Wilds of the North (all 1891). The first of these is hallmarked by a rhythmic harmony in the deployment of the trunks, a well-balanced compositional arrangement and a beautiful colour scheme. The main difficulty here, which Shishkin successfully overcame, was to depict convincingly the depths of the forest in twilight. The second painting is perceived quite differently; the trees of the foreground and the human figures (painted by Savitsky) are etched against an exquisite silvery background, which gives the picture a translucent arid elegant look.

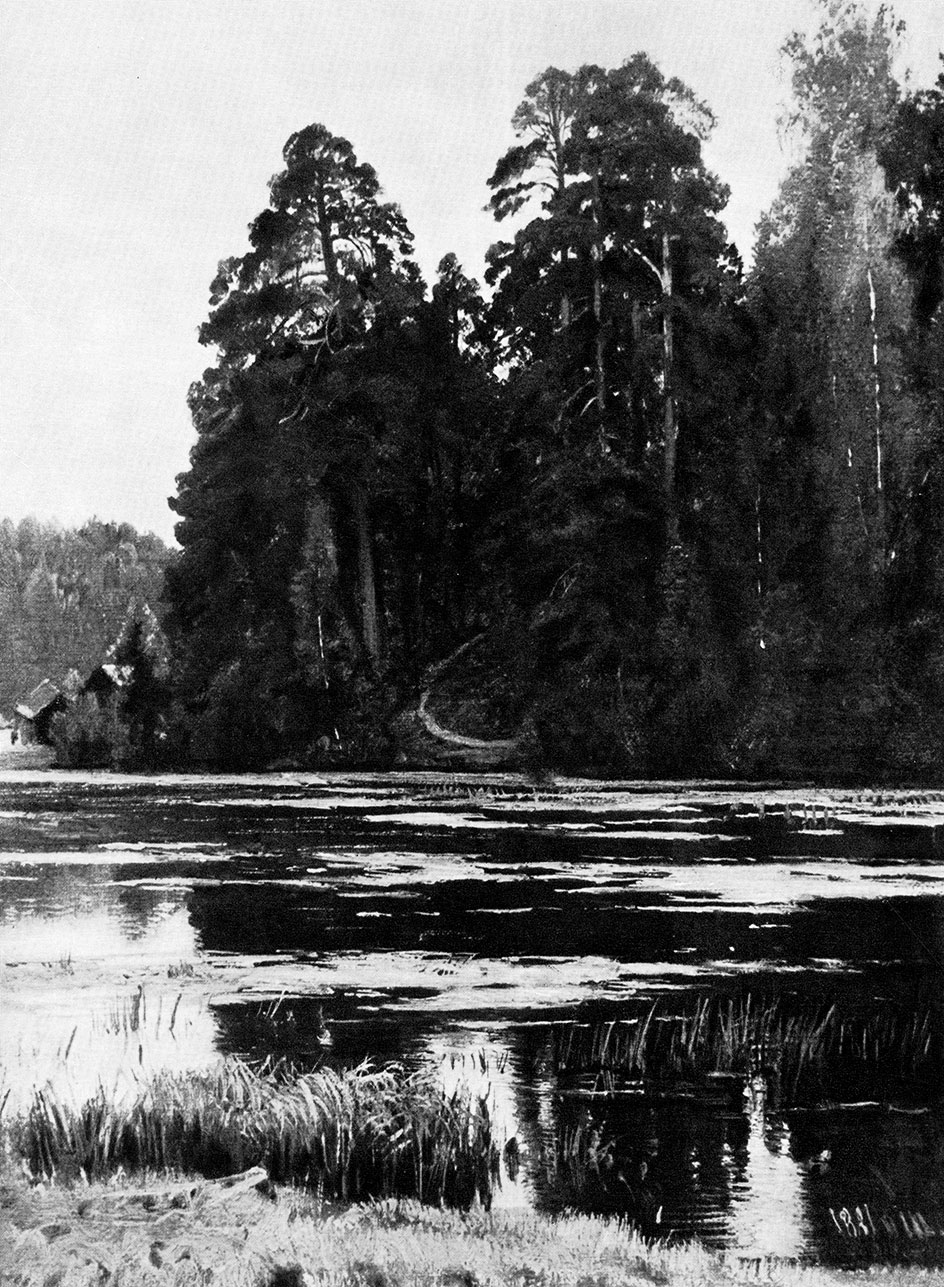

The pond. 1881 Oil on panel. 38×29.5 cm. The Savitsky Picture Gallery, Penza

The canvas In the Wilds of the North is a fortunate experiment by the artist. A lone, snow-coated pine stands proudly atop a rock overlooking a vast expanse of northern forest: the darkness of the night is emphasized by the glitter of the moonlit snow. The sharply contrasted illumination, the highlighting of the composition's conceptual centre, and the intensity of the blues were all new in Shishkin's work and bore witness to the boldness of his searchings.

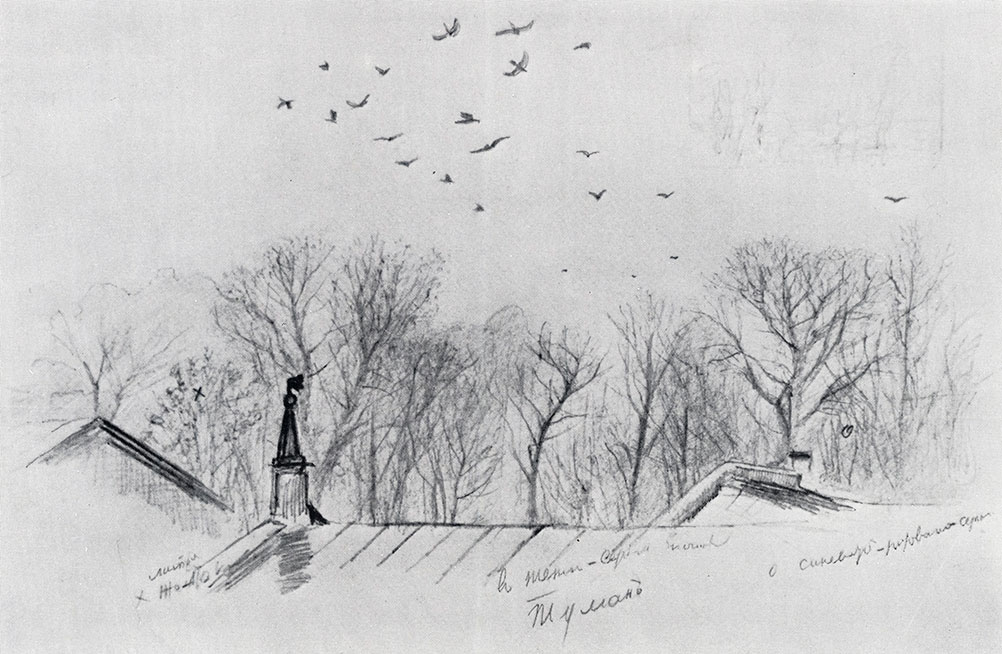

Sketch (Tree-tops above the roofs). 1884 Lead pencil on paper. 23.5×31.6 cm. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

At the end of 1891 Shishkin, together with Repin, organized in the Academy of Fine Arts an exhibition of his own latest studies. It was as if the mature master strove to outshine the younger generation of landscape painters which included Levitan and Konstan-tin Korovin by exhibiting scores of studies that bore witness to the ease of his painterly manner and to his vibrant feel for nature. Shishkin's works of the 1890s attest eloquently to the inexhaustibility of his talent. The exhibition played an important role in bridging the gap between the Academy and the Itinerants. After it, the most prominent of the Itinerants, Shishkin among them, were invited to teach in Russia's foremost art school.

Sketch (Bushes on a slope). 1884 Lead pencil on paper. 15.3×23.4 cm. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

In the last decade of his life Shishkin continued to work with enthusiasm on studies that to this day impress the viewer by their purity and sunlit radiance. Nor did he abandon landscape compositions. His large-format pictures are outstanding for their consummate craftsmanship, conceptual completeness and mature thought. The Kama Near Yelabuga, painted in 1895, is a work of epic grandeur.

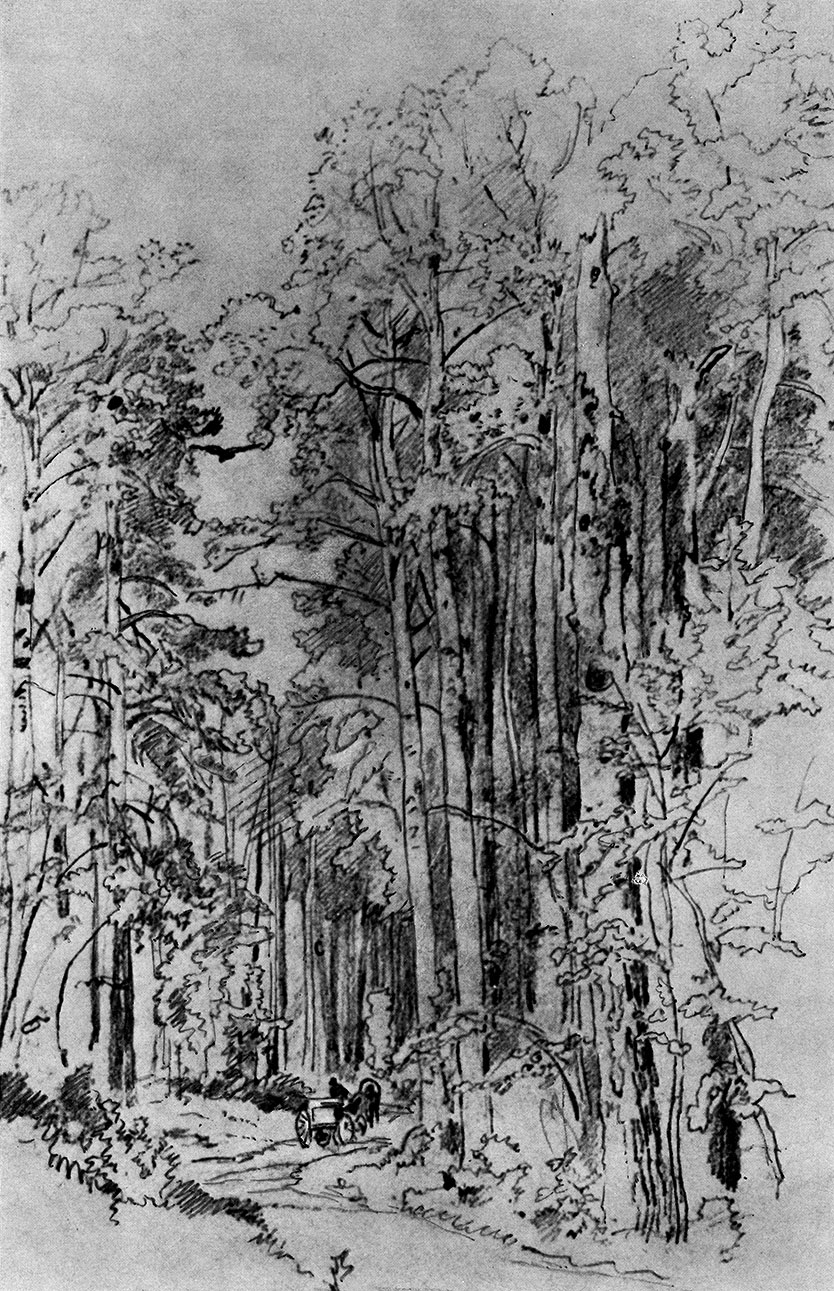

Aspens on the road to the kivach falls. 1889 Lead pencil on paper. 48×32 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

At the beginning of 1898 Shishkin, then sixty-six, produced a picture that revealed for the last time the artistic capabilities of this grand old man of Russian landscape painting. This was Mast-tree Grove, a canvas that synthesized, as it were, the various facets of the master's creative manner. A well-composed work and one of his largest, it produces an impression of monumentality, of stately grandeur and tranquillity. The motif is one familiar to Shishkin from childhood arid present in many of his previous works. The mast-tree grove near Yelabuga is painted here from almost the same spot as the picture Pine Forest (1872). It is, however, not the resemblance but the difference between the two works that is important. Many of the elements of the older work are discarded in Mast-tree Grove: foreground and background merge; the artist avoids the use of the coulisse type of composition and does away with superfluous details; everything is subordinated to the achievement of compositional, coloristic and conceptual expressiveness.

Abandoned windmill. Sketch for the similarly entitled picture (1898) Lead pencil on tinted paper. 39.6×51.7 cm. The Russian Museum, Leningrad

Rising towards the sky, the pines stretch beyond the limits of the picture. Several trunks in the centre are highlighted by the sun; at the right is a dense mass of green, at the left the transparent depths of the forest; side by side with the venerable giants young pines are growing; felled saplings span the rivulet, and in the foreground there are two butterflies on the wing. The mighty is here offset by the weak, the great by the small, the age-old by the ephemeral, but these contrasts are perceived as natural and truly expressive, not in the least bit contrived.

Soon after completing Mast-tree Grove, on March 8, 1898, Shishkin died.

His was an exceptionally active life. He created an endless number of pictures and studies, produced drawings of surpassing merit, did much to popularize and promote the art of engraving in Russia, was a long-time member of the Society for Circulating Art Exhibitions, and proved himself a dedicated, patient teacher.

To this day the profound thought and eloquent poetry of Shishkin's pictures are a feast for the eyes. A great Russian landscape painter, he has won the respect and recognition of his own country and the whole world.

© I-Shishkin.ru, 2013-2018

При копировании материалов просим ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://i-shishkin.ru/ "Шишкин Иван Иванович"

При копировании материалов просим ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://i-shishkin.ru/ "Шишкин Иван Иванович"