Shishkin as a graphic artist (A. Fiodorov-Davydov)

Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin occupies a place of honour in the brilliant galaxy of Russian landscape painters. He was the foremost landscape painter among the Itinerant artists of the 1870s and 1880s, and a vivid exponent of democratic realism. All his talents, his exceptional diligence arid persistence were devoted to the cause of promoting a national theme in landscape painting, to the creation of a truthful and meaningful image of Russian nature and especially of the Russian forest of which he was a connoisseur par excellence. As all Itinerant artists, Shishkin strove to achieve an uriidealized reflection of reality in his pictures, but his choice of motifs and their handling were always determined by the artist's own outlook and his own evaluation of that reality. The work of Shishkin, a democratically-minded artist, lends visual expression to Chernyshevsky's words: "...Man looks on nature with the eyes of an owner, and the things which seem beautiful to him on this earth are those linked with the happiness and contentment of human life."

Shishkin's prime interest lay in motifs expressing the wealth, abundance and power of Russian nature. He depicted giant forests, vast plains, and fields of corn. The image of the artist's native land as presented in his works is one of serenity and strength, of pure and simple beauty.

Shishkin has gone down in the history of Russian art primarily as a painter: his canvases are widely known and highly appreciated. No less significant, however, are the artist's graphic works - drawings, engravings, and lithographs. He was one of the most consummate draughtsmen and etchers of his time. No other Russian landscapist of that period was so involved with drawing as Shishkin, and none of the Russian painters of the time devoted as much time and effort to engraving as he did.

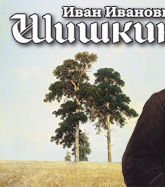

Woodland flowers. 1873 Etching. 9.6×8 cm

Shishkin first tried his hand at etching in 1853 while still a student of the Moscow School of Painting and Sculpture, but took it up in earnest in the early 1870s, when he joined the newly-organized Association of Russian Aquatint Artists. Etching attracted Shishkin by the relative rapidity of the process and the pictorial possibilities of the technique (a blend of line drawing and tonal effects). He worked for the most part with a needle, using soft-ground and aquatint finish.

Peasant woman with cows. 1873 Etching. 23.4×30 cm

Etching as a process involves intaglio printing on a hand-operated press. Setting great store by this technique, Shishkin attempted to create a special type of intaglio-relief printing which would allow to produce prints in large quantities. His experiments in this field did not yield any significant results, but they are characteristic of a democratic artist wishing to make his art accessible to the masses. In addition to engraving Shishkin also engaged in lithography.

Precise draughtsmanship lies at the root not only of Shishkin's drawings, but also of his paintings. The crucial role assigned by the artist to the drawing and his extremely accurate reflection of the objective world stem from the very character of Shishkin's art, which is based, in the words of Kramskoi, on the study of nature "in the scientific manner". True, all the artists of the realist school of Shishkin's time strove to convey faithfully their subject-matter, but whereas the landscapes of Savrasov and Vasilyev are characterized by a poignant lyricism, Shishkin saw his task as the telling of an unhurried and sober tale about nature; he was, in effect, its voluntary "chronicler". It is to this purpose that his strict drawing is subordinated, strict in the sense that it records every detail of the material object and conveys in artistic images everything gained from the study of nature. Shishkin once said, "One must seek nature in all its simplicity - the drawing must follow it in every little caprice of form."

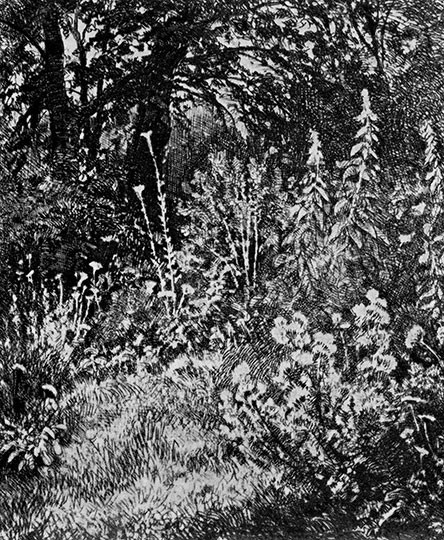

Edge of a pine grove. 1876 Etching. 8.8×13.3 cm

Shishkin's drawings are mainly of two kinds: plein-air scenes, of which there is a large quantity, and compositional pieces, of which there are relatively few. The former include both detailed works, long in the making, and rapid on-the-spot sketches, but both the first and the second are for the most part merely preliminary studies for pictures or thematically complete drawings. The majority of the artist's engravings, on the other hand, are original, self-contained compositions rich in content and marked by a high level of craftsmanship.

Scrutinizing Shishkin's drawings and etchings, we see all the depth and thoroughness, all the love and patience with which he studied nature, from the giants of the forest to the gossamer lacework of the leaves, from the intricate forms of the clouds in the sky to the most insignificant of woodland plants.

Among his drawings Oak-tree (1882) deserves special mention. The old trunk's mighty bulk, every little crack in the bark, all the flaws and scars inflicted by time and weather, all the widespread crooked branches and the luxurious growth of patterned leaves - all these are conveyed with the painstaking accuracy of what indeed seems "the scientific manner". In his handling of the tree the artist is fascinated by the unique beauty of its form and the rhythm of its curves, in which he strives to read the story of its life and growth. He assumes the role, as it were, of the tree's biographer. Shishkin's first-hand, studious knowledge of nature and his intrinsic understanding of it blend in this drawing into an indestructible whole: the most commonplace object acquires meaning, expressiveness and beauty under his brush. Thanks to his subtle feel for nature, Shishkin's precise sketches do not at all look like the lifeless, naturalistic drawings of a herbalist. The modest little etching Woodland Flowers (1873) is a striking piece not only because of the amazing accuracy of every minute detail, but also because of the artist's loving approach to the workings of nature. One gets the impression that the landscapist observed these unpretentious herbs and flowers with the same absorption and heartfelt interest with which a thoughtful portraitist looks into the face of his model to read his character and the story of his life.

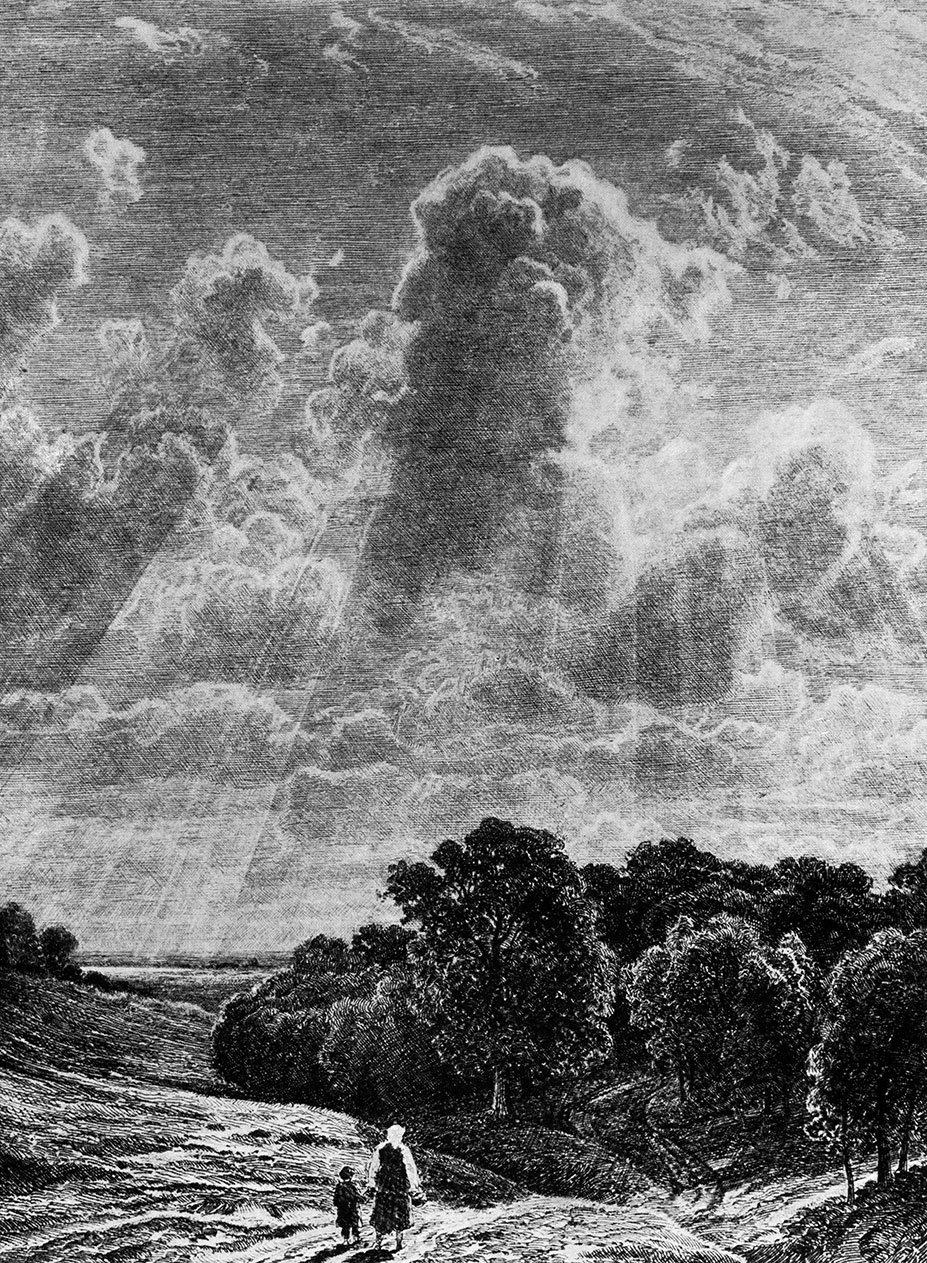

Clouds over a grove. 1878 Etching. 30.5×22.6 cm

This attitude towards nature and this ability to see and capture the silent life of objects helped Shishkin resolve the extremely difficult problem of sorting out the infinite complexities of the forest scene - intertwined branches without number, "tiers" of foliage one above the other, tangled pile-ups of mosses, trunks, dry twigs and trees blown down by the wind, clusters of herbs, leaves of grass and flowers. The artist's ability to convey the harmonious interaction of objects is well displayed in the drawing Fir-trees (1894), which captures every detail with amazing accuracy yet does not blur the overall impression. To have depicted the innermost depths of a forest the way Shishkin did in his etching The Taiga (1880) called not just for superb draughtsmanship, a keen eye and a sure hand, but for a perfect knowledge of the subject-matter - the fir-trees, rocks and mosses of the northern forest. Such a depiction could stem only from having often breathed the fragrant, moist air of the forest and observed first-hand its way of life, a life seemingly simple yet exceedingly complex, one which does not readily reveal itself to human eyes. Nothing else would have enabled the artist to convey so lucidly and so convincingly the complicated motif, the beauty and vitality of nature.

Shishkin was highly adept at pen drawing, never resorting to corrections or alterations. He would sometimes produce large, densely drawn sheets in this technique. The pen drawing somewhat resembles the etching technique in that the artist uses a needle, in much the same way as he would use a pen, to trace lines on the hard or soft ground covering the metal plate. Shishkin's pen drawings were often mistaken for engravings when he was still a student at the Academy of Arts.

Shishkin's lithographs done in ink and published under the title Studies in Pen on Stone (St. Petersburg, 1868) are, in eff ect, another variety of the pen drawing. An outstanding piece that bears witness to the flawlessness and versatility of Shishkin's drawing is the lithograph Oak-tree (1867).

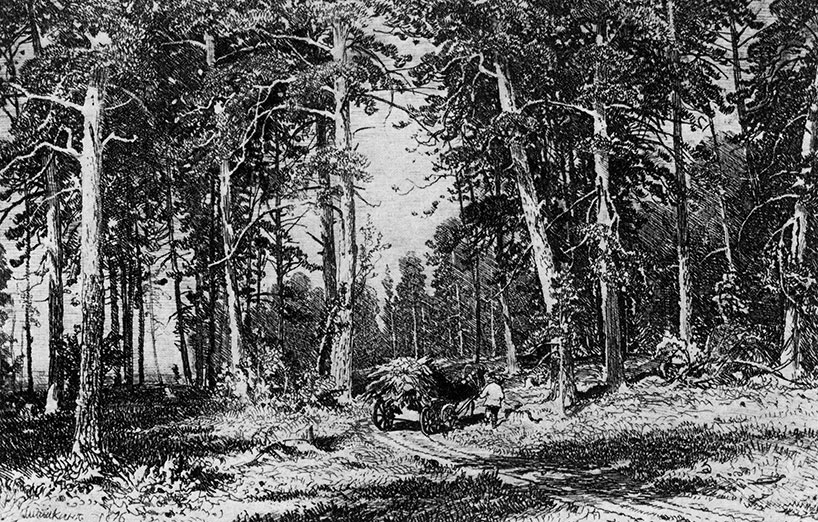

Ferns in the forest. 1877. Black chalk on tinted paper. 28.6×21.2 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Using short energetic strokes, the artist creates the impression that each leaf is fully delineated; he depicts the grass in straight lines, skilfully emphasizing the contrasts between the light and the deep background shade. The same is generally true of his exquisite pencil drawings.

The Apiary (1884) is a pen drawing in which Shishkin, for all his attention to the minutest detail, manages to preserve the integrity of the overall picture. He succeeds in conveying the volume and solidity of the objects - the hives in the foreground, the bushes in the near background, the pines on the distant slope, and at the same time imparts a spatial and highly plastic quality to the composition. The viewer is drawn, as it were, into the depths of the landscape as he scans the drawing from the bottom up. It should be noted that in spite of the detailed depiction of the objects demanded by the technique of pen drawing Shishkin succeeded in not "cluttering" the large surface of the sheet and in avoiding monotony in the distribution of the light and shade. This ability to reconcile meticulously drawn details with the oneness of the landscape is also characteristic of Shish-kin's better paintings.

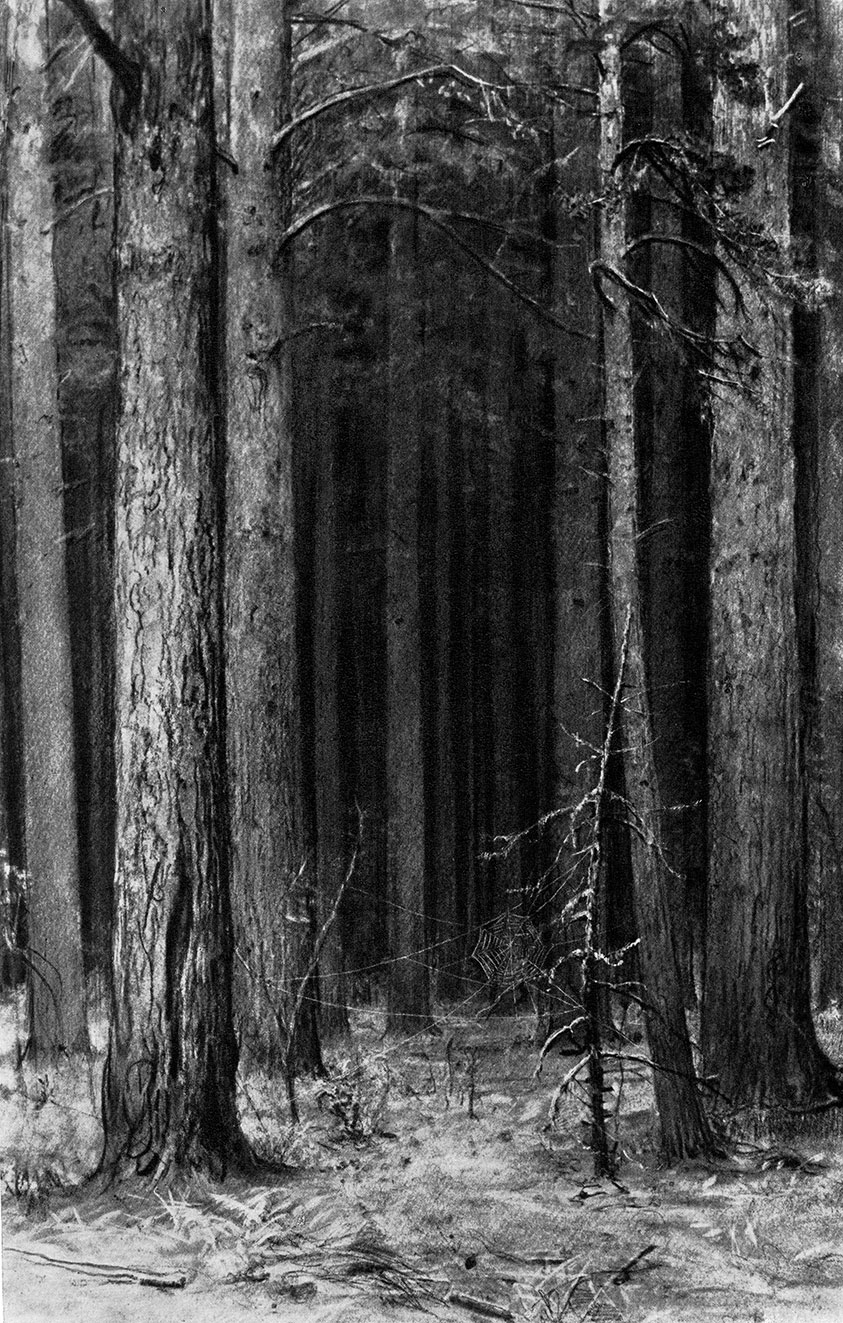

Cobwebs in the forest. 1880s. Black chalk on tinted paper. 44.8×30.5 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Shishkin's etchings are distinguished by the beauty of their lines and hatches. Cut into a metal plate and subsequently appearing in relief on paper, his lines acquire exceptional clarity and, when intermeshed, take on the elegance of filigree work. Shishkin used the intensity of the dark areas and the vibrancy of the unworked ones to good effect, imparting a sheen to the white parts of the paper - a quality distinguishing his prints. By repeating the etching process he achieved magnificent results in conveying the play of sunlight.

The light-and-shade effects in the etching Peasant Woman with Cows (1873) - the glittering, sunlit foliage against the dark tree-trunks - go a long way towards capturing the very essence of the forest. The expressiveness of the imagery is here coupled with the beauty of the technique.

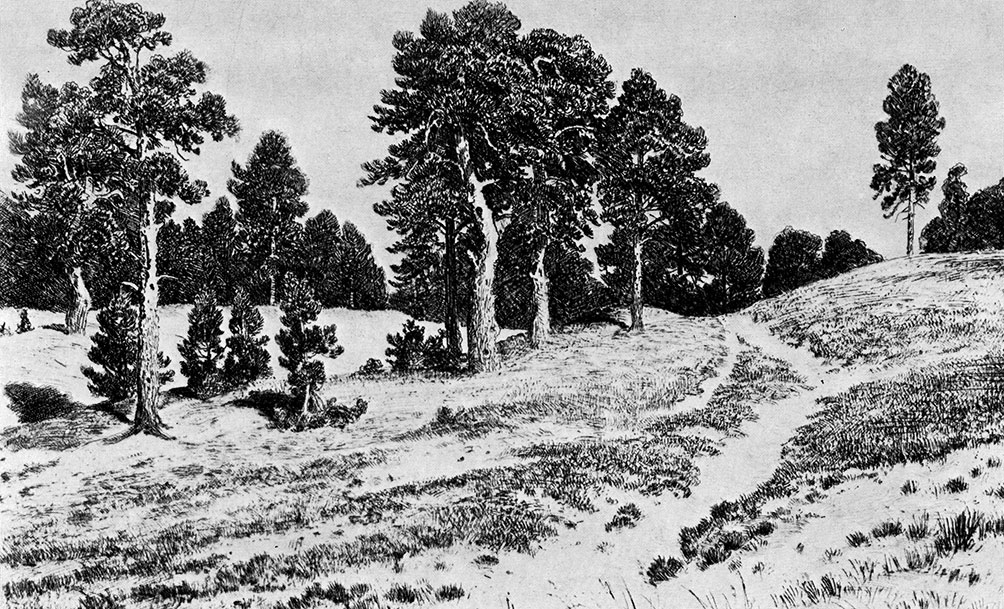

The sands. 1886. Etching, aquatint. 15.7×26 cm

Shishkin produced a large number of drawings and engravings in the course of his life: consequently, his creative evolution is reflected in his graphic art no less lucidly than in his painting. His graphic legacy contains a multitude of important achievements in the creation of a realistic image of Russian scenery.

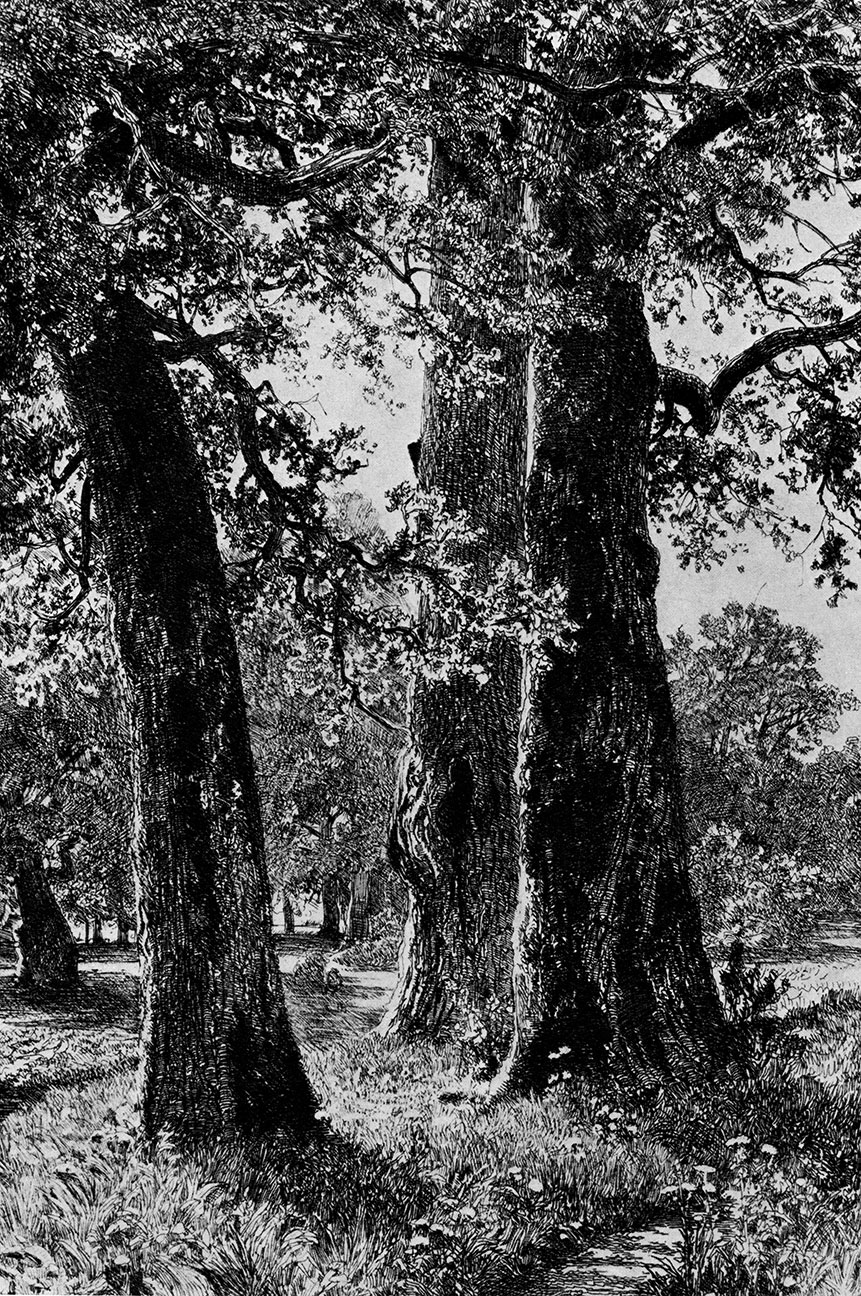

Three oaks. 1887. Etching. 21×14.7 cm

The lithograph Tangled Thicket (View of Valaam Island) (1860) is a typical example of Shishkin's work during his student years at the Academy. Valaam was in the 1850s a place much favoured by young artists: Shishkin was twice sent there to paint by the Academy, in 1858 and 1859. This piece sums up his impressions and sketches from both visits, as do two painted views of Valaam which in I860 earned him a gold medal and a trip abroad. Though an early work, the lithograph nevertheless shows the artist's affection for nature, even if it is manifested in imperfect form, namely in an excessive absorption with less important objects and details. The overall view is presented as a conglomeration of separate items; hence the congested picture, the merging of foreground and background, and the unevenly contrasted dark and light patches. Shishkin's school-bred romanticism is manifested in the selection of the lithograph's motif (a combination of huge rocks and dense undergrowth) and in the treatment of that motif whereby, thanks to the lighting, this depiction of nature acquires a peculiarly intimate character. The complicated techniques employed by the artist go back to the traditional methods of drawing on tinted paper, which include the use of whiting and also of scumbling - a device used to soften the lines of the drawing. Besides these, Shishkin resorted to scratching, which shows very clearly his progress in mastering the technology and the artistic possibilities of lithography. Shishkin's first teacher, Apollon Mokritsky, had every reason to regard this and similar works by his student as "the finest lithograph landscapes ever to be printed in Russia".

The romantic approach is also evident in his drawings of the 1860s done both in Russia and abroad. This was a period of searching and of broadening his outlook for the young artist. In a bid to make his landscapes more realistic and meaningful, Shishkin injects a narrative element into them, enlivens them with human beings and animals or depicts some transitory state of nature. A case in point is the drawing Herdsman with a Herd (1860s). The effective depiction of clouds (a motif that stems 'from the traditions of romanticism), the play of sunlight and the composition as a whole are here treated in a fully realistic manner, though there is a manifest desire on his part to tell the viewer as much as possible. Also characterized by "verbosity" are his pictures of the late 1860s which reflect the specifically Russian character of the landscape, for example Felling Trees (1867). The same detailed but as yet superficially descriptive tale of nature is present in the etching Forest Stream (1870).

The banks of the Kama near. Yelabuga. 1885. Etching. 13.4×25.5 cm

The next stage in the artist's evolution saw him overcome the outward complexity of his art to create an integral image whose particular facets are perceived only gradually as you absorb the overall scene. In the pictures Backwoods (1872) and Rye (1878) Shishkin presents nature simply as nature, and looks for his story in its innermost workings. In order to arrive at the same result in his graphic art he resorted to an intricate play of light and shade. Typical of this style is one of Shishkin's finest drawings, Ferns in the Forest (1877), a finished study which he twice repeated in oils. This is a complete and immediately perceivable view - a sunlit forest nook overgrown with fern. The horizontally positioned fronds and the movement of space as it recedes into the depths are very cleverly conveyed. Thus, a simple forest scene is translated by the artist into a lyrical landscape image.

Hunter on the Moor (1873) is an etching that in content comes close to a painting. In it, there is none of Shishkin's former detailed descriptiveness. The far-flung, boggy meadows, the high, cloudy sky and the flock of birds on the wing are meant to stress the vastness of the landscape. The consummate completeness of the picture, the profound and heartfelt image of his native land are all the result of Shishkin's long and painstaking observation of nature.

Shishkin was drawn early on to the theme of the infinite expanses of the Russian landscape. A typical example is the picture Midday in the Neighbourhood of Moscow (1869) with its endless fields, high sky and floating clouds. The festive, summer image of nature is also present in a number of the artist's etchings. A good example is the sheet Clouds Over a Grove (1878) where the sunlight streaming down on the fields and glades from behind the clouds is handled in the tranquil manner so typical of Shishkin. At times, though, he would succumb to the epic, gripping power of vast spaces, and it was then that canvases such as Amidst the Spreading Vale (1883) and etchings such as The Banks of the Kama Near Yelabuga (1885) would appear. All the austere, intrinsic power of the northern Russian landscape is concentrated in this work. A gorge with tall fir-trees is depicted; then, further away, a river and beyond that, stretching to the very horizon, a wooded plain. High in the sky a bird is soaring, adding to the vastness of the scene.

A fine sample of Shishkin's on-the-spot sketching is the drawing Forest Stream. Siverskaya (1876), in which the artist conveys the trunk, branches and needles of the pine knowledgeably and with a sure hand. The spatial entities are superbly constructed. It is interesting to note that for all its freedom the study shows a well-defined compositional arrangement.

A freer and more sweeping manner is evident in Shishkin's drawings of the 1880s and 1890s, Clouds and The Tops of the Pines. This, however, does not affect the accuracy of the artist's brushwork. So profound is the master's knowledge of nature that he captures the very essence of an object with but one or two lines. In Clouds the silhouette of the forest is made up of one swift contour with rapid shading inside it.

Though he never stopped producing line drawings, Shishkin began in the 1880s to draw in the painterly manner too. To convey light and air he took to working in charcoal and chalk on tinted paper. The painterly manner and the resultant tangibility of the air are evident in the drawing Cobwebs in the Forest (1880s). The Sands (1886) is an etching that well reflects Shishkin's fondness for plein-air drawing. It is notable for the dynamic and realistic treatment of the sand dunes overgrown with dry grass and bathed in sunlight. Though a monochrome print, it is nevertheless suggestive of colour - the sands are perceived as pale yellow, the needles of the pines as dark green. A look at this etching brings to mind the canvas Pine-trees Lit Up by the Sun (1886), a painting full of light, sun, air and the joy of life. Similarly, the picture Oak Grove (1887) is reminiscent of the sundrenched etching Three Oaks (1887), one of Shishkin's finest graphic works, remarkable for the way it conveys the sunlight and its reflexes on the grass, and the indented leaves set against the dark trunks. By portraying the scene against the light, Shishkin lends it an airy quality. At the same time, he makes skilful use of the reflexes to stress the shadowed forms, and so the black tree-trunks are not perceived as flat silhouettes. This is a work in which Shishkin managed to blend the graphic and the painterly elements of the composition into a harmonious whole.

"...He is by himself a school... a milestone in the evolution of the Russian laudscape": this is what Kramskoi said about Shishkin in 1872. We see in Shishkin a true lover of nature, a graphic artist par excellence who expressed in his landscapes the progressive thinking of his day. The imagery of his graphic art is truthful, meaningful and profound. The love of nature that engendered it and with which it is imbued reflects the ardent patriotism of an artist who served his country and his people well by unfolding before them the beauty and abundance of their native land.

© I-Shishkin.ru, 2013-2018

При копировании материалов просим ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://i-shishkin.ru/ "Шишкин Иван Иванович"

При копировании материалов просим ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://i-shishkin.ru/ "Шишкин Иван Иванович"